My research focuses on the counter-narratives of Indigenous peoples during the early period of exploration and colonization in the Americas. I have a strong commitment to diversifying the early American literary record and aim to give equitable space to silenced Indigenous points of view during the first contact period. The deafening Indigenous silences in early American explorer narratives has driven my research for the past five years. The lack of Indigenous representations in explorer works like la Relación, the 1542 narrative of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca has kept me awake at night wondering what was the Indigenous point of view to this first contact story? Bringing to light Indigenous points of view to the first contact period produces a more complete story of exploration and colonization. Juxtaposing, my research with my own personal experience as an undergraduate English student informs and deepens my understanding for the need to present a diverse and equitable literary and historical pedagogy. I found that I had little diversity in assigned readings outside the literary canon. For me, there is a personal obligation to teach marginalized, underrepresented, overlooked, and unconsidered literary authors. Exposure to unknown or excluded culture is an enriching experience that broadens the world.

I grew up the daughter of an enlisted Air Force father, born at the Navy base hospital in Charleston, South Carolina and when it was time for him to retire, I was graduating from high school in Northern Maine just two miles from the Canadian border. As a military dependent child, I was privileged and fortunate to experience a wide range of diverse people during my upbringing. When my father was stationed in the US territory of Guam I found value and enrichment in my development as a person from those around me who were non-Anglo. One such example was our Thai neighbor, her name was Belle and over the two years she and her husband lived next door, she taught me about her Buddhist faith, recipes from her homeland, and customs. Belle was not my only experience around cultures other than my own, my secondary schools were richly mixed with local Indigenous peoples (Chamorros), Filipinos, Thai, Vietnamese, Japanese, blacks, and whites. Realizing that the world is so diverse helped to inform my understanding of space and positionality and my realization that I can never understand what someone’s personal lived experience is because I did not experience it. One way that I can ensure my commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion is to start with a safe classroom environment that is judgment-free, where students can express themselves, ask questions, without fear of repercussions. A safe judgement-free classroom encourages students to critically think through difficult topics of race, ethnicity, identity, and sexuality that are deeply embedded in American literature.

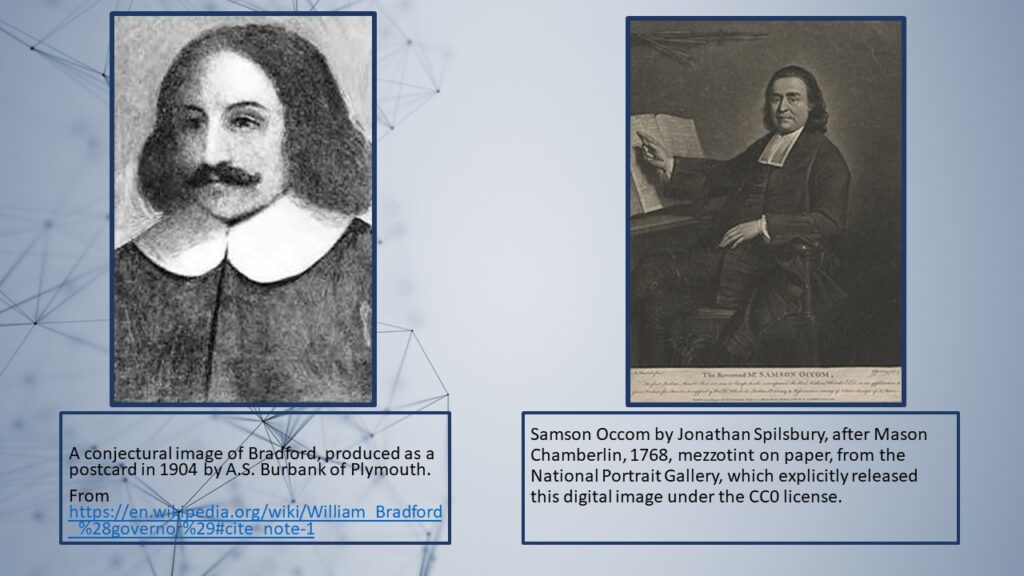

During my first Master’s degree in American Studies, I fell in love with early American literature, more specifically literatures of the American Revolution, and its rhetorical promises of freedom and equality. Quickly I learned the freedoms and equality was only for land owning, Christian, white males, and those promises did not exist for women, Indigenous peoples, slaves, Freemen, or poor white tenant farmers. Moreover, while these excluded ethnicities in early American democracy were at least somewhat represented in the current Norton early American anthology they were often being overlooked in early American classrooms. I think back to my experience in “American Lit I” and how my class was assigned to read Anne Bradstreet but not Phyllis Wheatly, we read William Bradford but not Samson Occom, never mind even considering that Indigenous textualities exist, flourish, and are plentiful beyond alphabetical works or codices. The lack of representation in classrooms reading assignments and widespread inequity in American literary anthologies informs my pedagogy and research. I am committed to teaching, talking about, and researching silenced, marginalized, and overlooked literatures.

Thinking back to all of the classes I have taught in the past six years, there is not one single class that I have conceptualized that has not engaged students with examples of literatures that are often overlooked on course reading lists. Even my syllabus for “History of Text Technologies” challenges students’ notions of what is a text? Asking them to consider Indigenous petroglyph rock carvings from the southwest and west coast of North America as textual and communicative not simply art. For my students who take my “Women in Literature” class, they read an eclectic array of women writers they may or may not have ever had the opportunity to engage with. Diversity within my pedagogy is not predicated on mere diverse and equitable representation in the assigned readings, but students are always presented with the social and cultural context in which minority authors wrote their works. Contextualizing literary works is important so that students who have never experienced literature from marginalized or silenced authors can understand nuances and rhetorical situations within the literary works. I feel that marked social, cultural, and equitable change happens in the humanities college classroom and it is here that we as instructors can make a positive impact for lasting change.